It’s been just over a year since Labour won the last General Election in the UK, heralding a new dawn after nearly fifteen years of Conservative Party rule. Already, the focus is distinctly familiar from previous years: many ordinary working people continue to remain disappointed by their standard of living and with the politicians in charge, exacerbated by a cost-of-living crisis. This is reflected in Kier Starmer’s plummeting in the polls, just as with his predecessors, while the polls predict a Reform victory across large swathes of the country for the forthcoming elections.

It’s beginning to feel like the UK is ungovernable, with the country having seen six prime ministers in the last ten years, compared to Tony Blair lasting on his own for the same amount of time. Beyond the presence of clickbait, social media, and tabloid press hyperbole, how did we get here, and what could have led to this situation, when disillusionment with politics remains so high among the general populace?

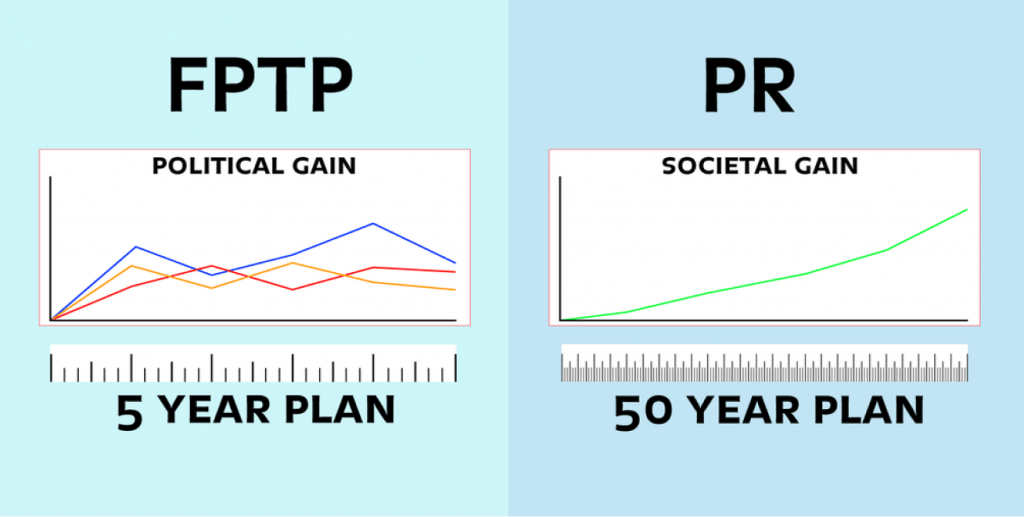

The UK’s insistence on clinging to first-past-the-post (FPTP) as an electoral system remains at odds with many of its European neighbours. The UK’s antagonism with the EU, culminating in Brexit, may in part be down to the fact that the UK’s voting system favours a ‘winner takes all’ approach, with parties in Parliament facing each other in adversity. This can be contrasted with the EU’s tradition of consensus, as reflected in the layout of the EU Parliament, in which MEPs work together as blocs according to different political spectrums under a proportional representation (PR) system. Furthermore, it could be argued that if the UK had adopted a voting system other than FPTP, it is possible that the UK could have ended up with a very different scenario from the one it faces now.

In essence, in FPTP, voters indicate on a ballot the candidate of their choice, and the candidate who receives the most votes then wins. This simplified view of the electoral process has been baldly labelled as “bad for voters, bad for Government and bad for democracy” by the Electoral Reform Society (ERS), which has long campaigned for change. It has ensured that a two-party system is embedded in the political system – a principle known as ‘Duverger’s Law’, after the sociologist Maurice Duverger – with little chance for other parties of making their mark (unless a coalition is formed, such as the one previously between the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats, or between the Conservatives and the DUP between the Brexit period). FPTP is still used in many Commonwealth countries, but not all: Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa have all changed from FPTP to another voting method. At the same time, within the UK itself, PR has been used to some extent in the devolved Scottish parliament and Welsh assembly with the Additional Member System (AMS), which mixes PR with FPTP. The London mayoral elections, too, have seen periods using a PR system, and will see a return to the system after the Conservatives axed it.

The legacy of FPTP in the UK is that many voters in ‘safe seats’ have simply given up voting for any party other than Labour or Conservative, given that under FPTP their votes would essentially be worthless. Those who have voted for anyone but the main two parties have found their vote effectively ‘wasted’, leading to voter apathy. In contrast, virtually all European countries, including EU member states and non-member states, employ PR, an arguably more representative electoral system. All of Europe? Well, except for one other country besides the UK that still clings to FPTP: Belarus, Europe’s last real dictatorship, and the only country in Europe to have the death penalty.

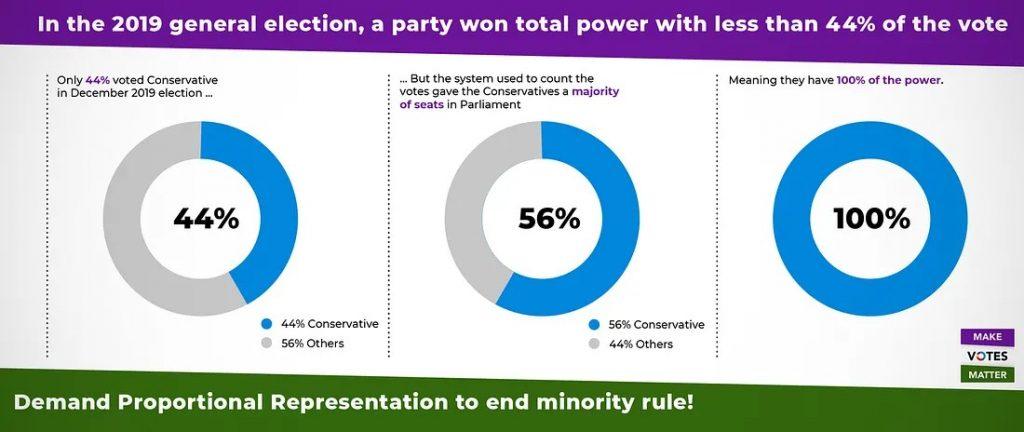

How these member-states implement PR varies, whether using the party list method, single transferable vote, or mixed member method. Overall, however, this has ensured a more precise representation of voter intentions, with the lineup in Governments accurately reflecting the results of elections (especially when using the D’Hondt method) in terms of seat allocation. This can be compared to the 2005 UK GE, where the Labour Party was victorious, despite winning as few as 35% of votes. Likewise, in 2019’s GE, only 44% voted Conservative, yet they gained an 80-seat majority – and, with it, 100% of the power.

By contrast, PR has meant a greater choice for voters where their voting intentions can strongly match their beliefs, which in turn has encouraged greater turnouts for elections. Not only does this mean fewer ‘wasted votes’, but it also means that candidates have to campaign in all districts, rather than just the ‘swing seats’.

In the UK, the Brexit campaign, while stretching far back with many Eurosceptic roots, was truly set rolling when the Conservatives pledged to hold a referendum in their manifesto for the 2015 general election. The Tories would go on to win that election despite only 36.9% of the votes cast. Along the way, the Liberal Democrats and Greens, who under PR could’ve stated the case for their parties as presenting a genuine third way that embraces Europe, found themselves out cold.

Opponents of PR have long held that it would ensure a presence in parliament of right-wing groups such as Reform (and before them UKIP and The Brexit Party). In fact, the opposite could be the case. Meanwhile, the experience of several other EU member states has shown that the views of more extremist wings can often be neutralised. In the general election held in the Netherlands in 2017, all major parties refused to form a coalition with Geert Wilders’ right-wing Party for Freedom (PVV – Partij Voor de Vrijheid), effectively denying the PVV any chance to participate in Government policy. Whether the same will apply to the current wave of right-wing populist parties in Europe, such as Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AFD) or Le Pen in France, remains to be seen.

The UK did have a referendum on changing the electoral system in 2011. This was to replace the present FPTP system with the ‘Alternative Vote‘ (AV) method, rather than PR. Under AV, voters rank candidates in order of preference. The ballots for the eliminated losing candidates are then redistributed until one candidate is the top remaining choice of voters. If two candidates are left with equal ranking, an ‘instant runoff’ allows head-to-head comparison – hence the use of the term ‘Instant-runoff voting’ as an alternative name for AV. The referendum to change to AV was rejected by 67.9% of voters, with the ‘No to AV’ campaign spearheaded by the same people who would go on to campaign for Brexit. Noticeably, the areas that voted ‘Yes’ above 50% to changing to AV were Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh Central, Glasgow Kelvin, and six voting areas in London – the same places that voted overwhelmingly to remain in the EU referendum. Since then, the 2011 referendum has been barely mentioned.

Before this, there were attempts to introduce PR into the UK parliament during the early 1900s. In the 1970s, FPTP produced weak majority governments in the UK, while part of a coalition – ironically, the very situation that detractors of PR have claimed is its major flaw. In more recent times, the Liberal Democrats and Greens have advocated for PR.

If the Conservatives had gone into the 2015 election under a PR system of Government, they could have found their commitment to holding a referendum on the UK’s EU membership under sustained scrutiny. Members of Labour, the Greens and the Liberal Democrats could have stared down the Eurosceptic backbenchers. In addition, the likes of the Greens, forever shut out of Government under FPTP, could have exerted pressure under PR to guide in liberal progressive policies. Instead, the UK has found itself stuck in a never-ending two-party system that sees no sign of opening up – a gift for the Conservatives and Labour, who are loath to change the system, but a curse for other parties, whose only chance of making a change is via a coalition with the two main parties. This is even though at successive Labour conferences, a clear majority of members have signalled their desire to see the UK change to PR. The fact that FPTP benefits the Tories and Labour so well has ensured that a change to PR remains an unlikely prospect.

But how would PR work in practice? As an experiment, I’ve tried to imagine what the U.K. system would look like under a PR party-list system. It’s a complicated task. The aforementioned Electoral Reform Society point out that “rather than electing one person per area, in Party List [i.e. Proportional Representation] systems each area is bigger and elects a group of MPs that closely reflect the way the area voted. At the moment, we have 650 constituencies, each electing 1 Member of Parliament (MP); under a Party List system, we might have 26 constituencies, each electing 25 MPs”.

Theoretically, the number of these constituencies under PR — which I’m going to call ‘voting super areas’ (VSA), as awful as that sounds, to distinguish them from current constituencies — doesn’t have to be 26. A mathematical calculation will tell you that 50 VSA under PR with 13 MPs makes 650; however, the number of MPs — i.e. seats — in each of these VSA could fluctuate from 10 to 13, divided proportionally with the top three or four main parties, based on the population density of each VSA, making the total number of MPs in the country total 650. Each of those constituencies would be a coalition of MPs, based on voter figures. The Boundary Commission, the body that is responsible for balancing the UK’s constituencies’ sizes under our current FPTP system, would have a huge task.

Nonetheless, there are already precedents that we can go by. The most obvious is the fact that while the UK was a member of the EU, it took part in elections to the European Parliament under PR. Going by the results of the 2019 European Parliament election — the last that the UK was involved with — you can see that the UK was split into just 12 super-regions (technically 13 if you include Gibraltar, which was included but has its own Parliament as a British Overseas Territory):

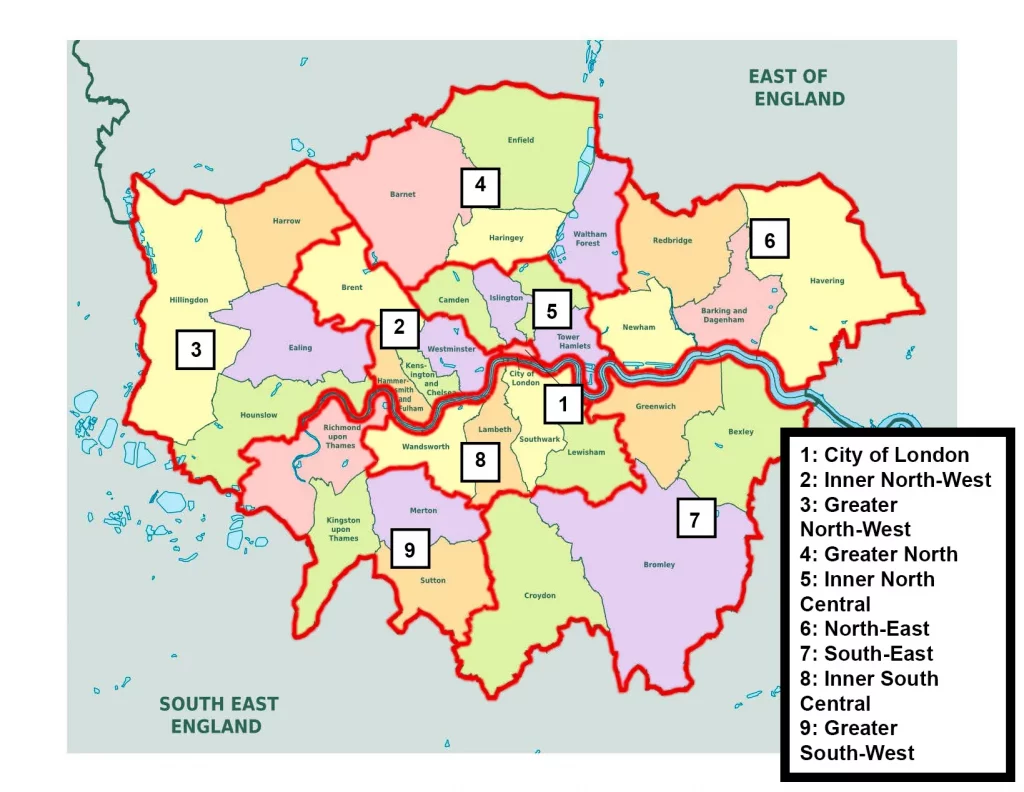

Taking the example of London, as you can see, the city was counted as one overall super-region, for which the Brexit Party, the Liberal Democrats, Labour and the Greens all won seats, sending MEPs to the Parliament in Brussels — all of which then joined their own pan-European bloc of like-minded fellow MEPs (the current iterations of which can be viewed here).

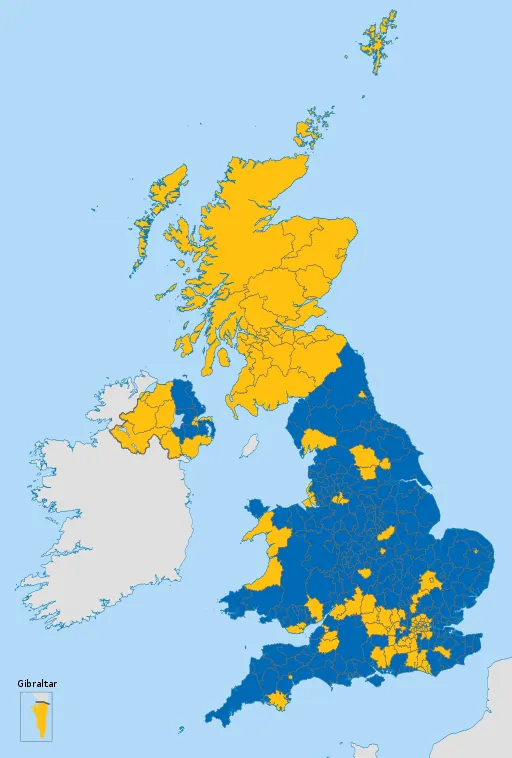

The UK’s referendum on the EU in 2016, meanwhile, split England, Wales, and Scotland into ‘Voting Areas’ based on Councils, each comprising several constituencies (Northern Ireland kept to its normal constituency boundaries). Wales had around 22 of these voting areas, while Scotland had 32. Due to its much larger size, England inevitably had vastly more voting areas (blue areas in image voted overall to leave; yellow to remain):

The method used for the EU referendum still produced more voting areas than would be possible under PR. At the other end of the spectrum, the method used for the European Parliament elections in 2019 had an extreme version of super-regions/VSA — only 12 (13 including Gibraltar, as mentioned). However, the point nonetheless remains that the methods used in both the European Parliament elections and the EU Referendum redrew the voting maps of the UK accordingly, which proved that it can be done.

Let’s go back to what the UK under PR would look like. In London, the sheer amount of people per capita would require there to be several VSA. A good way to divide up these areas would be to have an equal number of boroughs — 4 — in each (except for the City of London (CoL), which would be its own VSA due to its unusual status as a separate entity to the rest of London as a whole). This is illustrated in the image below, which I have modified using Photoshop to divide a map of London’s boroughs into these VSA. Each VSA could then have three MPs for each borough, leading to 12 MPs in each constituency area. There are actually echoes of this in the fact that before 1999, London was represented during European Parliament elections as several single-member constituencies: London South West, London North West, London South East, London North, London Central, London West, London East, London South Inner, and London North East. Where the CoL was included in those VSA, and how it operated accordingly, is unclear.

The permutations of this could apply not just in London, but in the UK’s other most populated cities — Birmingham, Glasgow, and Manchester most prominently, all of which have their own systems of boroughs or administrative areas. Yorkshire as a whole, meanwhile, contains nearly as many people as the whole of Scotland, so it would require more than one VSA. Meanwhile, much less densely populated areas, such as Northumberland or Argyll & Bute, would require only one VSA. This system would lead to a fairer and, yes, more proportional system, in which people would be motivated to vote.

It wouldn’t be perfect, of course. To give an example, Hackney, where I’m from, would see three MPs elected as part of an Inner North Central VSA, as mentioned. Those three MPs might be one each from Labour, the Liberal Democrats, and the Conservatives (though the latter only command a small amount of support in the borough); or those three might be one each from Labour, the Liberal Democrats, and the Greens. How the Conservatives would work with MPs from other parties in practice in VSAs would await to be seen — there would most likely be a process of horse-trading — but the aforementioned coalition between the Tories and the Lib Dems after 2010’s GE illustrated that it is possible, not to mention the also aforementioned previous history of cross-party London MEPs being elected to European Parliaments under PR during the period that the UK was a member-state of the EU. That could still leave candidate MPs from other parties not represented — and therefore other, smaller parties could still find themselves sidelined under PR. Nonetheless, they would still be sidelined less than under FPTP, in which only one party is represented in a constituency. A PR system would be particularly beneficial to the Liberal Democrats and the Greens, who would have a bigger representation in a VSA.

This video from Australia, describing their system under PR, is a good explainer:

As you can see, six candidates are whittled down to three via the votes being reallocated using a Single Transferrable Vote (STV) system. Despite this clear enough explanation, the transition from FPTP to PR remains a very complicated process. You can see this when comparing Australia’s neighbour, New Zealand:

New Zealand also uses PR, but with a mixed-member system (MMP), which retains elements of FPTP. The comparison with the U.K. system, and how New Zealand’s PR MMR system would apply, is once again complicated, but is elucidated to some degree in this video:

So too are the different versions of PR that can be applied. Wikipedia lists some sixteen different versions of PR, including models such as ‘Bi-proportional Appointment’, which applies mathematical modelling to election results to achieve proportionality.

Whether a UK system under PR should adopt STV or MMR methods remains a moot point. Either would still be more democratic than the current system, even while STV uses FPTP.

In any case, many people in the UK want our election system changed, as part of a wider shake-up that should include a reevaluation of the House of Lords as an entirely unelected body (something that Starmer had promised to tackle), along with the establishment of a written constitution. Labour For a New Democracy is one of them. A coalition of pro-PR groups, such as the aforementioned ERS, Make Votes Matter (MVM) – who I volunteer for, for disclosure – and Labour Campaign for Electoral Reform (LCER), Labour For A New Democracy (they’re serious people who don’t appear to do acronyms) plan to continue to take the case to Labour for PR, backed by 188 Constituency Labour Parties (CLPs) around the country, despite Starmer’s prevaricating. The fact that so many CLPs back PR makes the campaign an increasingly prominent issue.

PR may not be a panacea for all the UK’s troubles, and it is naïve to think that it would solve every problem that the country faces in one fell swoop. But adopting it would lead to a revitalised political system that would alleviate the worst aspects of cronyism and factionalism. PR shows another way. New Zealand achieved it in 1996, albeit by keeping elements of FPTP, as mentioned, via MMR. It must happen if we are to truly call ourselves a modern European democracy in the 21st century — whether in the EU or not. Otherwise, the UK cannot continue to call itself a serious democracy while we are stuck in the merry-go-round of a two-party system.

Comments are closed.